What Is a Koan?—

When I was a young Zen student, my teacher gave me a Koan to meditate on. A Koan may be thought of as a puzzling story meant to jar us out of our addiction to solution. They are often described as spiritual lessons, and are used to invite inquiry into the nature of the human condition. Historically, they have also been used to exemplify the meaning of Buddha’s teachings, by way of parable.

One of the most popular Koans is that of the man eating a strawberry on the edge of a cliff. The source of this story is thought to be the Pali Canon, which is the collection of texts in which Buddha’s doctrinal principles were first recorded.

The Koan—

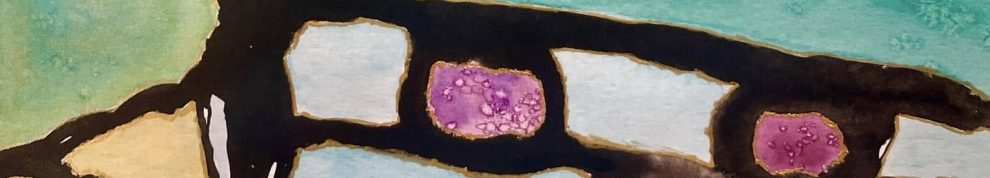

A traveler runs into a tiger. The tiger chases him until he comes to a precipice. Holding on to the root of a wild vine, he swings over the edge. Looking down, the man sees another tiger far below, waiting to eat him. The vine is the only thing that is tethering him to life. But his problem does not end there. Two mice, one white and one black, are gnawing at the vine. Right at that moment, the man sees a delicious strawberry growing on a bush, within reach. Grasping the vine with one hand, the man plucks the strawberry with the other hand. How sweet it tastes!

My Commentary—

This Koan is an invitation to seize the moment. We tend to live as if “waiting for the other shoe to drop.” We worry about things we have no control over and we agonize over that which is inevitable, like death.

The ability to totally give ourselves over to the present moment is more easily said than done, as we’ve been conditioned to plan for the future so as to stave off danger. And although the dangers are no longer in the form of tigers, the inner anxiety and fear is the same.

We are reminded daily of all the things that we need to worry about, from our retirement plans, to our to our job security. We’re told to make sure we’ve slept enough, stepped enough, consumed enough protein, and made enough money.

Sure, there’s good sense in planning, but at some point, good-planning turns into over-planning. I remember a day in the Zen temple, when our teacher, the “Roshi,” was answering questions. He had been talking about things like this, and someone asked “But, isn’t planning important… what if you’re trying to get into Law School or something?” And he simply said, “Then fill out the application.”

What he was saying is that while there’s certainly a proper place for planning and preparing, it often becomes obsessive, especially when “mapping out our future” takes the place of living our lives. Fill out the application and then go on with your life. The extra worry is like “wearing two heads,” as we say in Zen.

We are that guy hanging from the vine! Our fears and obsessions are the tigers. Our minds are on call, all the time, for potential emergency.

Watching our thoughts, in meditation, we are amused to find ourselves vacillating between disaster preparedness and dreams of excitement to come. But then we slip into the past, repeating scenarios from days gone by. In the course of a moment or two, we’ve skipped over the timeline of our lives, jumping from past to future until we can’t recall how we got onto the current train of thought. We catch ourselves playing out fantasies of what did happen, how it might’ve happened, if it will happen and how to prevent it from happening.

We want to be ready for “when it happens,” but if and when it does, we continue to look ahead toward the next “what if.” Because our minds are habituated to reaching and striving.

We become obsessive “problem solvers.” As if that was the point of existence. But in Buddhist teachings, the ups and downs aren’t something to be solved. They’re just part of life’s ceaseless movement. Like the tides, problems come and go. And inner peace is only found when we allow these natural shifts to occur of their own accord, in their own time… and when we allow for all of it—the the joy, as well as the grief.

The most important activity in authentic Zen practice is no activity at all… ”just sitting,” with no goal, no expectations, and no judgments. Just sitting is called Zazen. The only job to do is to watch your thoughts. Just be fully present without trying to achieve anything. Not even enlightenment.

There will be certain fleeting moments… a flash perhaps, where you will catch yourself enjoying the here and now… which is to say, delighting in the strawberry without being distracted by anything else… without worrying about all the tigers hiding in the past and in the future, waiting to get you.

To put it simply, the Koan asks us: Can you be totally surrendered? Can you live in a state of acceptance? Can you let go of control? Can you enjoy the fruit, even though disaster could strike at any second?

Pema Chödrön used to have a sign on her wall that read:

Only to the extent that we expose ourselves over and over to annihilation can that which is indestructible be found in us.

That guy on the cliff is on the precipice of the unknown, totally exposed to this possibility of annihilation. The point is that all of us are, as well, but we choose to run from it. We’re lost in our stories. We’re distracted… we’re busy.

But when we stop and confront this moment, exactly as it is, our fully surrendered state opens us up like a flower to the sun. No longer tethered to our stories, our fears or even our fantasies, we are vulnerable. And something new is born from this erasure.

In this way, as we say in Zen, we are born and we die every day… every moment. Birth and death, birth and death, continually.

This is why we are encouraged by our teachers to “sit with the fear.” Because if we’re courageous enough to sit and not run, something beautiful will reveal itself. But don’t go looking for it!

Of course there are things to do and plenty to worry about. And when it’s time to do it, we will do it. This way of living requires having faith in yourself. When it’s time to eat, we eat. When it’s time to sleep, we sleep. And when it’s time to march… we’ll march!

But, apart from that, worry will only destroy the present moment. And this moment, like every passing moment, is a gift that we will never get back again. This strawberry might be the last strawberry we’ll ever eat.

*This was originally posted on Awaken.com.