What Does Art Have?—

Aesthetics has always asked, What does all good art have in common? Is there some common denominator? What is art, anyway? What is beauty? There may be more than one answer to those questions. Sometimes art does different things and serves different purposes. Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes stood as art (and not Brillo Boxes) because of what they were “saying” about consumer culture. I spoke of that here.

As Immanuel Kant said, art invokes within us, a sense of awe and deep pleasure. Like nature, it takes us where words cannot.

This helps us understand what art does, but still feels inconclusive, as far as what art has. Or is.

Yet, after taking great interest in aesthetics as a philosophy student, through my 20s, I still couldn’t answer, at least to my own satisfaction, the question: What does all good art have in common? Even if there are multiple answers, or none at all. (Maybe it’s like asking what religion is… there is no common denominator. Only what scholars have termed “family resemblances.”)

Nonetheless, it is only now, through direct experience, after 30 years of painting in watercolor, and writing poetry… and writing in general, have I started to get a glimpse of what I feel to be a truthful response.

But first, indulge a memory with me… I promise, it’ll bring us back to the question of art!

The Storm Rolling In—

I remember running to the classroom window, pushing aside those heavy beige, vinyl drapes, to see the sky turning dark, and the sudden burst of light that illuminated the asphalt outside. Then the rumble. And the anticipation it brought on… how loud will it get? How close will it come?

It wasn’t merely because we rarely get ferocious storms in Southern California. My excitement, which I still feel when storms approach, reveals more than that. Alluding to Kant again, who recognized that nature most powerfully elicits that sense of awe, that all art is but a kind of exemplar of the sublimity we find in nature, we find our clue as to what makes both art and nature riveting in the same way. And, the storms outside of LA were all the more so.

It was in the Midwest somewhere… we heard it coming. Like a high speed train roaring. Getting closer. As we ran to open the door, the wind pushed it against the wall. Yet, we couldn’t resist and so we charged into the flurry and out into the middle of the street and it felt like the world was coming to an end. We stood and watched with wild hair and our arms outstretched against the electric jet stream of warm air. We were buzzing. Suddenly turned the heavens poured out a river and in 20 minutes, it was gone.

Jason Bonham’s Led Zeppelin Experience—

I felt that frenzied excitement when I saw John Bonham’s son and his Led Zeppelin Experience last year. My own reaction was totally unexpected. But that’s the whole point, as I’ll explain below. A genuine reaction to art is, and has to be, totally uncontrived. And to do that, the art will possess some element that is wild, like the storms above. More on that in a moment. When those first notes of Immigrant Song exploded, I was, at that moment, like a teenager. I remember jumping up out of my seat, straining on my tiptoes to see… at any cost and discomfort… perhaps managing to blurt out Oh My God a few times because I couldn’t say anything else. Because I couldn’t believe what I was seeing or hearing. Because teenagers do crazy things. Because teenagers have energy (except for when they can’t get out of bed).

Presence (The location of Beginner’s Mind)—

More to the point, a youngster’s sense of physical presence exceeds their mental ruminations. And since thinking is draining, the result is vitality… and there has always been an inverse relationship between presence and the degree to which you are in your head. Meaning, the more you are in your head, in the world of thoughts, the less present you are. It starts when we become adults. When we become rational. Teenagers haven’t gotten there yet. So, they are still free.

That’s why we adults have so much fun at events like that, we don’t just act like teenagers for that moment in time. We become as kids again. Because we are in our bodies… not in our heads. The music (and all art… and nature) is a conduit for feeling. We are feeling the music, and leaving the world of thought behind for that moment. And thus, we have no sense of “should be’s.” We act naturally, in all our exuberance. In Zen, this is what it means to have a “Beginner’s Mind.” To be blissfully ignorant of the world’s ideas and judgments. And so, free to express oneself authentically.

Crazy… It’s The Same Criterion for Both The Artist and The “Feeler”—

It’s not holding back. When a singer moves us it’s because she’s not holding back. She’s willing to sing at the edge, right at the place where her voice might crack. But she’s not concerned with that. She’s not playing it safe. She’s not tightened or constricted or self conscious. It’s what good writers do. It’s what good actors do. She’s doing, in her art form, what we wish we could do in life. She’s purging emotions as we wish we could. And thus, there is a purification process in the art exchange, for both artist and viewer, through the feeling of release.

And so, we’ve come around to what I feel answers the question… What does all good art have in common?

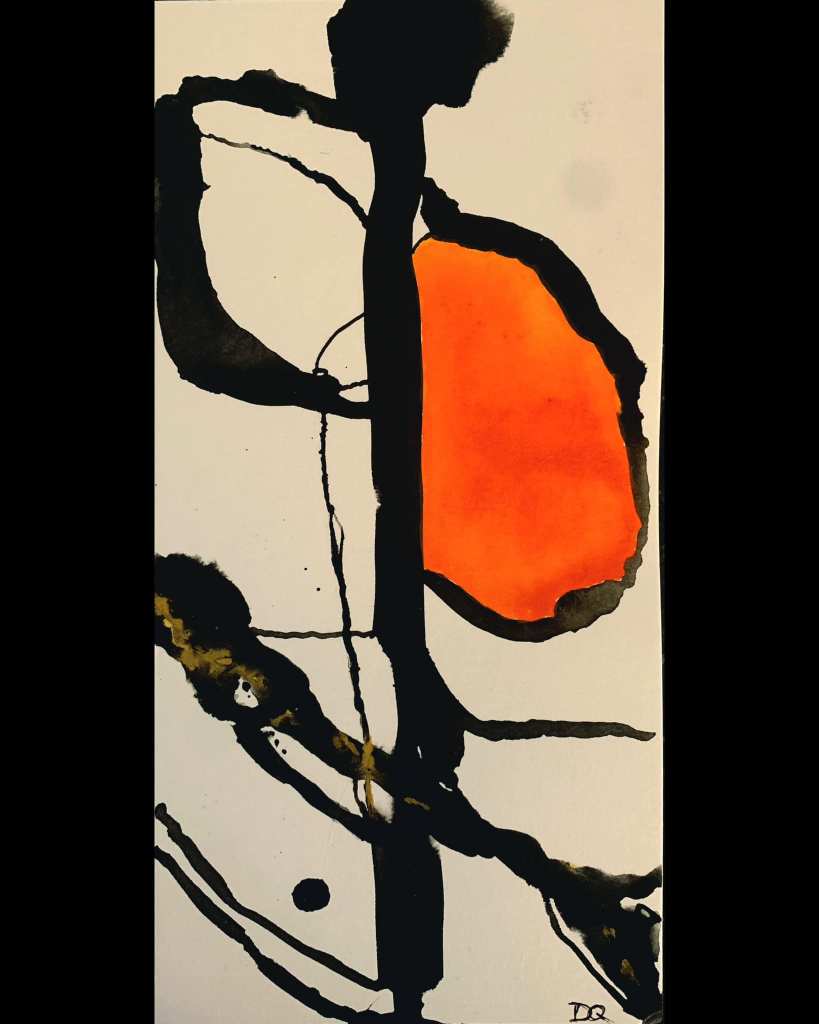

It could be said this way: It’s the element of crazy. Something wild and crazy has to happen in that painting, in the dance, in the routine, in the song, in the performance.

Why? Because art unleashes something that has been laid to rest in the depths of our soul… Ultimately, it’s fear. At the very least, it reveals what we wouldn’t do in “real life.” In that sense, it is therapeutic. It is revelatory. It reveals the capacity to let go and to abandon ourselves. It reveals possibilities we thought weren’t for us… to be whimsical, carefree and unguarded. To be fearless.

Which ultimately means… To be FREE.

When asked, “what does freedom mean to you?“ the iconic singer Nina Simone simply said, “to be fearless.”

But we don’t dare, in our everyday lives. We were taught to be rational. We’re careful. We’re measured. We’re prudent. We’re tight. We don’t dare take a chance!

The Wild Stuff Makes it Special—

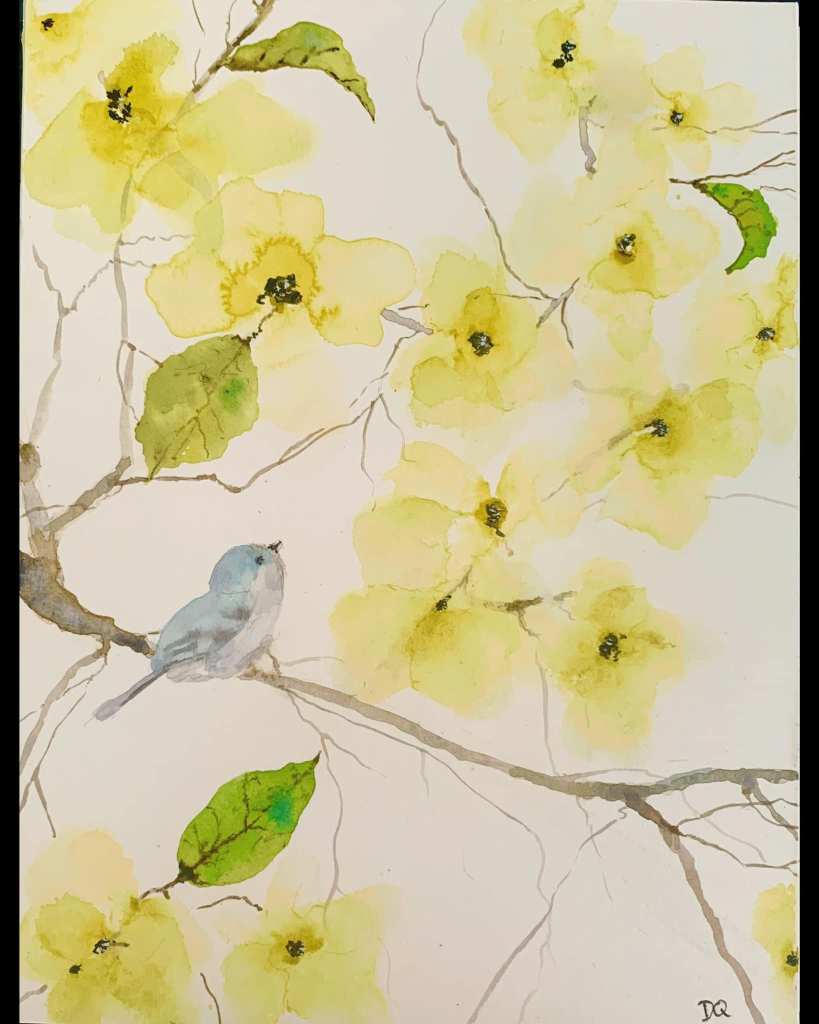

It’s the big, bold tree stroke in the foreground of a painting. The stroke that makes you think, as an artist, or someone watching from behind, as you’re about to do it, “Oh no!… You’re going to ruin it!“ because the background was done so carefully. Reason will dictate… Leave well enough alone.

That’s where art steps in. Art messes it all up, like crazy hair. Like that sky that turned black before it opened up and flooded the streets for those 20 minutes.

Art is where convention is, ipso facto, irrelevant, since creativity is by its very definition, the birthing, or the configuration of something new. And this process often looks weird or wild or simply… crazy. To be clear, this doesn’t and shouldn’t mean harmful. Nor necessarily loud. But it does mean bold… in myriad ways. Think John Cage in his silent symphony. Think Marina Abromovic, in her meditative, interactive art. Think Cindy Sherman in her performance pieces, which feature herself as objet d’art, in different guises. All pushed boundaries and convention in their own weird and wonderful way. Keep in mind, to sit still is bold. To be quiet is bold.

In a more prosaic example, I remember seeing footage of Joe Cocker singing at Woodstock, as a girl… I asked my mom what was wrong with him… why was he shaking? Yet I couldn’t take my eyes off of him.

Beginner’s Mind—

It’s that element of crazy, again. It feels like freedom—the most basic human requirement. It’s the quality of being uncontrived. The Zen masters call naturalness. And it springs forth from the “Beginners Mind,” which is a mind that is free of concepts. In plain terms, it is a mind that is free of the “should be’s”. Free from fear of failure. Free from the corruption of other people’s judgments and opinions. Free from the rules of convention that we spoke of. Totally spontaneous and totally yourself. Joe Cocker let the spirit move through him (and the drugs). Cindy Sherman had to disappear, in a sense, in order to become the characters she became.

A Strange and Perfect Pairing of Chutzpah and Selflessness—

It’s chutzpah. It’s bold. It’s brave. It breaks the rules. It can’t be tamed. It’s why every new genre has to break from the past. It’s rock and roll. And by rock and roll, I don’t only mean rock and roll as we think of it today. Using it loosely at this moment, I mean that which possesses that quality of boldness that I have been speaking of… Vivaldi, by this standard, was as rock and roll as it gets, with his reputed flamboyance and innovative spirit. He just couldn’t “plug in.” He was wild, like all rockers, who do whatever the hell they want to do. They scream and yell and kick and move their hips, like Elvis. They growl like Gregg Allman and Leon Russell… just growl on tune!

But, in some measure of paradox, the artist has to lose himself, through the boldness. Or, said differently, the boldness must not come from ego, lest it be contrived, which is the antithesis of beginner’s mind. And the same is true for the viewer. And together, the journey is taken into abandon. And this is freedom.

It’s what good acting does… The actor loses himself. He lets go of control, for that moment. He becomes the character, as effort gives way to effortlessness. It’s why Joshua Bell, the violinist, once said that at the moment of performance, all practicing is let go of. He has to trust at that moment that it’s in his bones.

The Enzo Brings it Back Around—

The Japanese Enzo displays this element of naturalness and spontaneity. Which is wild and irrational in its appearance of not-caring. And… free. Like all good calligraphy, you would never “go back over it.” Because perfection has nothing to do with it. Because perfection is in the head! The question is rather, is it “felt?” Not, “did you think it through?” Were you inspired at that moment? Was it free? Was it confident (and thus, bold)? Was it authentic?

Like me, at that concert… when we act naturally, out of beginner’s mind, there is no limiting or constraining sense of “should be”… there’s no sense of embarrassment. There’s no sense of “not good enough.” Like the wild storm, you just pummel through and do what you came to do… with no inhibition.

For a plant or a stone to be natural is no problem. But for us there is some problem, indeed a big problem… The true practice of zazen is to sit as if drinking water when you are thirsty. Then you have naturalness. ~Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (Shunryo Suzuki)

In this way, art conveys what we wish we could be in “real life.” We long for that spirit of abandon. It’s why we love road trips; it’s why we love falling in love (“we are not in our right mind”… it’s been called a kind of temporary insanity, but we love it). That’s why we miss being children.